|

| @ Ed Hansons |

The British-born Princess Ludwig of Löwenstein-Wertheim was a passenger on the ill-fated St.Raphael that was piloted by Captain Leslie Hamilton and Colonel F.F Minchin. The plane, set to race across the Atlantic in a westward direction, left the Upavone Aerodrome near Salisbury at 7:30 a.m. on August 31, 1927. The plane was a Fokker monoplane. The plan was to fly to Ottawa, Canada, a distance of 3600 miles.

The Dublin correspondent for The Times telegraphed the paper to say that St. Raphael reached the Irish coast at 10:00 a.m. It passed over Thurles, County Tipperary at 10:40 a.m., and then headed out to sea between Garumma Island and Irish More in the Aran island. When the plane was last seen, St. Raphael "was flying well" as it started across the Atlantic.

Princess Ludwig was the plane's financial backer. She wanted to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. She sat on a wicker chair in the cabin of the plane at the back of the eight petrol tanks that occupied most of the cabin space.

The princess arrived by car shortly before the Roman Catholic bishop of Cardiff, led a simple religious service.

"God Bless you all," he said. "May you have a safe journey. We shall not forget to pray for you." The Archbishop blessed the monoplane and sprinkled it with holy water.”

The plane never reached its destination. It has been assumed that the plane crashed into the sea, and all three occupants were killed.

Lady Anne Savile was born in 1864 as the youngest daughter of the 4th Earl of Mexborough. On May 15, 1897, she married Prince Ludwig of Lòwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg at the Roman Catholic Church of the Assumption on Warwick Street, Regent Street, in London.

Lady Anne was accompanied by her mother and given away by her brother, the Hon. John Savile. Her brides were Lady Mary Savile (her sister), Miss Beatrice Savile (cousin), Lady Ethel Keith-Falconer, Lady Margaret Crichton-Smith, Lady Charlotte Graham Toler, and Miss Muriel Wentworth. The Hon. Herbrand and the Hon. Harold Alexander "acted as train bearers."

Prince Ludwig's supporter was Baron Bolko von Ochritz, Chamberlain to the German Imperial Court.

Among the friends and family who were guests at the wedding included: Princess Ernest of Löwenstein, the Spanish ambassador and Countess Casa Valencia, the Marchioness of Bute, the Count and Countess of Lützow, the Earl and Countess of Rosse and Lady Muriel Parsons, the Earl and Countess of Oxford, the Earl of Norbury, the Countess of Kildare, the Countess of Granard and Lady Eve Forbes, the Countess of Caledon, the Countess of Verulam, the Countess of Dundonald, among others,

The Earl and Countess of Mexborough hosted a luncheon for the wedding party at their home in Dover Street. In the afternoon, the newlyweds received by telegram an apostolic benediction from the Pope.

The Prince and Princess left the reception for Ditton Lodge, Thames Ditton, which had been placed at their disposal by the bride's mother.

Prince Ludwig had come to England in search of an heiress, where he "applied for an introduction to society to a man of an aristocratic family, but who is possessed of neither money nor scruples," according to the Marquise de Fontenoy's column on September 1, 1898. This "blue-blood undertook to introduce the Prince into those particular houses where he was most likely to meet with an heiress."

But following his marriage to "little" Lady Anne, the prince failed to pay the price for his introduction to society or "the commission due upon her dowry.” Legal proceedings were instituted against the prince in London.

Anne's father, the wealthy 4th Earl of Mexborough could have paid the amount demanded, but, according to the Marquise, the earl was “heartily sick of his German son-in-law and [was] not inclined to move a foot to help him."

Lord Mexborough "had never been favorable to the match." He disliked the prince "on general principles, but likewise for his un-English manners." He deeply regretted Anne’s marriage to Prince Ludwig.

At first, Anne “chivalrously took up the cudgels on behalf of her truant husband," insisting to all who would listen that those hunting for her husband "were disreputable blackmailers."

After only a few months of marriage, the prince "vanished completely" and did not turn up until eighteen months later in the Philippines.

The scandal grew uglier as Prince Ludwig fled the "disreputable marriage brokers," for failing to pay the sum of money "they had advanced him" to woo Lady Anne. The prince went to Europe, where he "suddenly vanished.” A year later, he was found "killed by American bullets" in the Philippines, "garbed in the distinctive dress of a Filipino rebel."In the Philippines, he got involved with the "European adventurers" who were involved in the insurrection against the United States. On several occasions, he was nearly arrested by the Americans for being a spy. On March 16, 1899, he was "struck by several bullets fired by soldiers of the Oregon regiment in a house where rebels had been concealed."

Lady Anne was accompanied by her mother and given away by her brother, the Hon. John Savile. Her brides were Lady Mary Savile (her sister), Miss Beatrice Savile (cousin), Lady Ethel Keith-Falconer, Lady Margaret Crichton-Smith, Lady Charlotte Graham Toler, and Miss Muriel Wentworth. The Hon. Herbrand and the Hon. Harold Alexander "acted as train bearers."

Prince Ludwig's supporter was Baron Bolko von Ochritz, Chamberlain to the German Imperial Court.

Among the friends and family who were guests at the wedding included: Princess Ernest of Löwenstein, the Spanish ambassador and Countess Casa Valencia, the Marchioness of Bute, the Count and Countess of Lützow, the Earl and Countess of Rosse and Lady Muriel Parsons, the Earl and Countess of Oxford, the Earl of Norbury, the Countess of Kildare, the Countess of Granard and Lady Eve Forbes, the Countess of Caledon, the Countess of Verulam, the Countess of Dundonald, among others,

The Earl and Countess of Mexborough hosted a luncheon for the wedding party at their home in Dover Street. In the afternoon, the newlyweds received by telegram an apostolic benediction from the Pope.

The Prince and Princess left the reception for Ditton Lodge, Thames Ditton, which had been placed at their disposal by the bride's mother.

Prince Ludwig had come to England in search of an heiress, where he "applied for an introduction to society to a man of an aristocratic family, but who is possessed of neither money nor scruples," according to the Marquise de Fontenoy's column on September 1, 1898. This "blue-blood undertook to introduce the Prince into those particular houses where he was most likely to meet with an heiress."

But following his marriage to "little" Lady Anne, the prince failed to pay the price for his introduction to society or "the commission due upon her dowry.” Legal proceedings were instituted against the prince in London.

Anne's father, the wealthy 4th Earl of Mexborough could have paid the amount demanded, but, according to the Marquise, the earl was “heartily sick of his German son-in-law and [was] not inclined to move a foot to help him."

Lord Mexborough "had never been favorable to the match." He disliked the prince "on general principles, but likewise for his un-English manners." He deeply regretted Anne’s marriage to Prince Ludwig.

At first, Anne “chivalrously took up the cudgels on behalf of her truant husband," insisting to all who would listen that those hunting for her husband "were disreputable blackmailers."

After only a few months of marriage, the prince "vanished completely" and did not turn up until eighteen months later in the Philippines.

The scandal grew uglier as Prince Ludwig fled the "disreputable marriage brokers," for failing to pay the sum of money "they had advanced him" to woo Lady Anne. The prince went to Europe, where he "suddenly vanished.” A year later, he was found "killed by American bullets" in the Philippines, "garbed in the distinctive dress of a Filipino rebel."In the Philippines, he got involved with the "European adventurers" who were involved in the insurrection against the United States. On several occasions, he was nearly arrested by the Americans for being a spy. On March 16, 1899, he was "struck by several bullets fired by soldiers of the Oregon regiment in a house where rebels had been concealed."

A search of his body revealed a passport signed by the rebel leader, Aguinaldo, who granted permission to Mr. Wertheim "permission to enter the lines of the rebels at will."

Princess Ludwig was wealthy in her own right and never received a penny from her husband's family.

In 1913, the princess traveled to New York aboard the Majestic "to submit to a practical test the self-leveling cot of which she invented for the prevention of seasickness." She became "a frequent visitor to America, and a familiar figure in New York,” until the outbreak of the first world war.

The princess, “who inherited no little of the eccentricity for which members of her brilliantly gifted family are somewhat celebrated, was certainly a woman with an independent streak. Even after her “brutal husband” abandoned her and fled to the Philippines, Anne refused to resume her maiden name. The Marquise de Fontenoy noted that the princess continued to use her husband’s title because the German and Austrian courts and her husband’s family refused to accept the marriage as equal, and “took the stand that she, in consequence, had no right to his name or to his rank.”

Although the Löwenstein-Wertheim family acknowledged that Saviles were a historic family, they “took exception” to Anne’s mother who had Jewish blood. [Anne’s mother’s family, the Raphaels, were actually Catholic Armenians.) Anne “failed to realize” that she was a “far more important personage in England and foreign society as the daughter of an English earl of ancient lineage than as the widow of an outlawed and outcast German prince.” When the war broke out in 1914, her family implored her to give up the name and resume her maiden name to “avoid trouble. She refused, but she soon discovered that her German title was a hindrance to her daily life. Hoteliers would not receive her as a guest so she adopted the alias, “Mrs. Ellis.”

But she still aroused suspicion because of the princely coronets on her luggage and linen. Was she a foreign lady of high rank masquerading as a German spy? She was a German national, and when it became necessary for her to register under the Aliens Restriction Order, she gave the following particulars: Surname (Ludwig); Christian name (Anne); nationality (German); occupation (Princess Löwenstein-Wertheim). She signed her name as Anne Löwenstein-Wertheim.

Thus, she was charged with “furnishing false particulars” when she checked into Victoria Hotel in Manchester. The princess registered as “Evelyn Ellis, British nationality of 118, Porchester Terrace, London.” All of the information was false, including the address. As an alien, she was also in violation of traveling more than five miles from her registered place without a permit.

Anne was in Manchester because she was making inquiries about airplanes. After making several telephone calls to local aviation firms, she called in at one local airplane company. She asked the manager if he could make a plane “capable of carrying four passengers and with a 200 horsepower engine.”

The earl responded: “Yes; we have always called her the ‘John Bull’ of the family; she is most patriotic.” He was also questioned about her passion for flying. The earl told the court that Anne had “done a great deal of it in various parts of the world.” This included a flight across the Channel from Sussex to Dieppe and also had flown in Egypt.

She had made “various flights since,” and, she had told him in May 1914 that she had wanted to give the government an airplane. This did not happen because of the outbreak of the war.

Lord Mexborough added that his family “had always greatly disapproved of his sister’s craze for flying.” He said that this disapproval had led her “to resort to subterfuges.” He also believed that she had been in communication with the Air Board on flying matters, and she was “very anxious to do something in the flying world for the benefit of this country in the war.”

The Princess was fined for the false particulars but was acquitted of “any motive in any way inconsistent with her loyalty to her native country.”

For some years, the princess lived in London at 8 Upper Belgrave Street, although she would spend time at Arden Hall in Helmsley, the home of the Earl and Countess of Mexborough.

The Court Circular, published daily in the Times, noted when the Princess would travel to St. Moritz or to the Continent with her sister, Lady Mary Savile.

The princess had not originally planned to join the St. Raphael as a passenger, even though she had flown several times with Captain Hamilton. She was considered one of Britain's first airwomen, having taken up flying in 1914. In 1923, she entered the King’s Cup Air Race in England, and she got Captain Hamilton to pilot her plane. In 1925, the princess and Hamilton left London for a flight to Paris. The first part of the trip was successful, but all trace of the plane was lost as the pair passed over Folkestone. Ships received wireless messages to watch out for the plane, but it was not until the next day when they appeared at Pontoise, France, “where they were forced down by engine trouble.”

The princess was “too much of a veteran” to have been bothered by the plane’s failure. She was one of the first women to fly across the Channel, and she was also an ardent sportswoman, who was fond of skiing. She invented a new ski “to prevent jumpers from suffering fractured ankles in falling.” When Captain Hamilton announced his plans to fly from London to Ottawa, the princess offered financial aid.

As one of the plane’s backers, she made it known that she wanted to be the first woman to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. Her brother, the Earl of Mexborough, and other family members “entered strenuous objections.” Anne, however, was not to be daunted.

A week before the flight, “there was a considerable mystery about the Princess’s whereabouts,” and one media report said that she “intended to outwit the opposition by making a quick getaway from her relatives by hopping aboard the plane before its departure.”

This plan came to naught because of the premature disclosure, much to the Princess’ distress. Bad weather forced the delay of the flight by nearly a week, and it was said that the “daring Princess began an intensive effort to get her family to agree on her flight.”

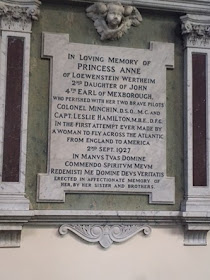

The princess' body was never found. A plaque in her memory is on one of the walls at her family's church, St Raphael's Roman Catholic Church in Kingston.

In 1913, the princess traveled to New York aboard the Majestic "to submit to a practical test the self-leveling cot of which she invented for the prevention of seasickness." She became "a frequent visitor to America, and a familiar figure in New York,” until the outbreak of the first world war.

The princess, “who inherited no little of the eccentricity for which members of her brilliantly gifted family are somewhat celebrated, was certainly a woman with an independent streak. Even after her “brutal husband” abandoned her and fled to the Philippines, Anne refused to resume her maiden name. The Marquise de Fontenoy noted that the princess continued to use her husband’s title because the German and Austrian courts and her husband’s family refused to accept the marriage as equal, and “took the stand that she, in consequence, had no right to his name or to his rank.”

Although the Löwenstein-Wertheim family acknowledged that Saviles were a historic family, they “took exception” to Anne’s mother who had Jewish blood. [Anne’s mother’s family, the Raphaels, were actually Catholic Armenians.) Anne “failed to realize” that she was a “far more important personage in England and foreign society as the daughter of an English earl of ancient lineage than as the widow of an outlawed and outcast German prince.” When the war broke out in 1914, her family implored her to give up the name and resume her maiden name to “avoid trouble. She refused, but she soon discovered that her German title was a hindrance to her daily life. Hoteliers would not receive her as a guest so she adopted the alias, “Mrs. Ellis.”

But she still aroused suspicion because of the princely coronets on her luggage and linen. Was she a foreign lady of high rank masquerading as a German spy? She was a German national, and when it became necessary for her to register under the Aliens Restriction Order, she gave the following particulars: Surname (Ludwig); Christian name (Anne); nationality (German); occupation (Princess Löwenstein-Wertheim). She signed her name as Anne Löwenstein-Wertheim.

Thus, she was charged with “furnishing false particulars” when she checked into Victoria Hotel in Manchester. The princess registered as “Evelyn Ellis, British nationality of 118, Porchester Terrace, London.” All of the information was false, including the address. As an alien, she was also in violation of traveling more than five miles from her registered place without a permit.

Anne was in Manchester because she was making inquiries about airplanes. After making several telephone calls to local aviation firms, she called in at one local airplane company. She asked the manager if he could make a plane “capable of carrying four passengers and with a 200 horsepower engine.”

In court, it was noted that it was not an offense to purchase a plane, but “it was suspicious that a German princess should have adopted the conduct the defendant did in trying to acquire an aeroplane which would be capable of flying across the North Sea.” The princess could dispose of documentary evidence and “carrying over the sea any escaped German officer who might be at large in this country.”

The detective, who arrested the princess, said that “her explanation of her visit” to the factory was because she wanted an airplane to “help do war work.”

The princess’ brother, Lord Mexborough, testified on her behalf. He told the court that his sister “had a craze for flying.” He added that the only relationship his sister had with Germany “was the occasional visits paid to that country during the two years of her married life.” He added that she had “no German or anti-British leanings.”

Lord Mexborough was also asked about his sister’s patriotism. “You have known her to be throughout her life a thoroughly patriotic British person?”

The detective, who arrested the princess, said that “her explanation of her visit” to the factory was because she wanted an airplane to “help do war work.”

The princess’ brother, Lord Mexborough, testified on her behalf. He told the court that his sister “had a craze for flying.” He added that the only relationship his sister had with Germany “was the occasional visits paid to that country during the two years of her married life.” He added that she had “no German or anti-British leanings.”

Lord Mexborough was also asked about his sister’s patriotism. “You have known her to be throughout her life a thoroughly patriotic British person?”

The earl responded: “Yes; we have always called her the ‘John Bull’ of the family; she is most patriotic.” He was also questioned about her passion for flying. The earl told the court that Anne had “done a great deal of it in various parts of the world.” This included a flight across the Channel from Sussex to Dieppe and also had flown in Egypt.

She had made “various flights since,” and, she had told him in May 1914 that she had wanted to give the government an airplane. This did not happen because of the outbreak of the war.

Lord Mexborough added that his family “had always greatly disapproved of his sister’s craze for flying.” He said that this disapproval had led her “to resort to subterfuges.” He also believed that she had been in communication with the Air Board on flying matters, and she was “very anxious to do something in the flying world for the benefit of this country in the war.”

The Princess was fined for the false particulars but was acquitted of “any motive in any way inconsistent with her loyalty to her native country.”

For some years, the princess lived in London at 8 Upper Belgrave Street, although she would spend time at Arden Hall in Helmsley, the home of the Earl and Countess of Mexborough.

The Court Circular, published daily in the Times, noted when the Princess would travel to St. Moritz or to the Continent with her sister, Lady Mary Savile.

The princess had not originally planned to join the St. Raphael as a passenger, even though she had flown several times with Captain Hamilton. She was considered one of Britain's first airwomen, having taken up flying in 1914. In 1923, she entered the King’s Cup Air Race in England, and she got Captain Hamilton to pilot her plane. In 1925, the princess and Hamilton left London for a flight to Paris. The first part of the trip was successful, but all trace of the plane was lost as the pair passed over Folkestone. Ships received wireless messages to watch out for the plane, but it was not until the next day when they appeared at Pontoise, France, “where they were forced down by engine trouble.”

The princess was “too much of a veteran” to have been bothered by the plane’s failure. She was one of the first women to fly across the Channel, and she was also an ardent sportswoman, who was fond of skiing. She invented a new ski “to prevent jumpers from suffering fractured ankles in falling.” When Captain Hamilton announced his plans to fly from London to Ottawa, the princess offered financial aid.

As one of the plane’s backers, she made it known that she wanted to be the first woman to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. Her brother, the Earl of Mexborough, and other family members “entered strenuous objections.” Anne, however, was not to be daunted.

A week before the flight, “there was a considerable mystery about the Princess’s whereabouts,” and one media report said that she “intended to outwit the opposition by making a quick getaway from her relatives by hopping aboard the plane before its departure.”

This plan came to naught because of the premature disclosure, much to the Princess’ distress. Bad weather forced the delay of the flight by nearly a week, and it was said that the “daring Princess began an intensive effort to get her family to agree on her flight.”

The princess' body was never found. A plaque in her memory is on one of the walls at her family's church, St Raphael's Roman Catholic Church in Kingston.

If you liked this post, please buy me a latte

Thanks for elaborating on the life of "Lady Anne Savile" what an upside downside interesting life she had and such a short marriage period with her husband. Perhaps not as short as her sister Lady Mary Savile .

ReplyDeleteAs a brief aside "A plaque in her memory is one one ... (one two many one I think, sorry for the pun)

Thanks for information I had been researching F. Minchin.

ReplyDelete